A Thousand Winters Ago

by Les Davis

| After breaking camp on a foggy July morning in 1975, the leadoff survey crew loaded up and headed on down the Missouri River by johnboat. We were searching for evidence of archaeological sites eroding out of riverside terraces. Well downstream from the jump-off point at Virgelle, Mont., we spotted a buried but eroding prehistoric midden, a garbage dump exposed in the cutbank. Standing in one of the boats, the rising sun in his eyes, project field supervisor Steve Aaberg from Bozeman used binoculars to inspect the shadow-obscured north river bank. Twelve feet below the sagebrush-covered surface of the cutbank, he saw what turned out to be a thin, horizontal layer of mammal bones, mixed with fire-broken rocks and wood charcoal. |  |

Above: Study of a Pronghorn [Antelope] (by Karl Bodmer) |

Stopping and going back upstream to check it out, Aaberg recognized the bones as those of North American pronghorns. This remarkable find was especially interesting since we hadn't expected to find any pronghorn kill or processing sites north of Wyoming and the Great Basin - where the hunting of pronghorns was traditional, even during Late Prehistoric times.

The fieldwork that followed at the Lost Terrace archaeological site, and analyses of excavated remains, have since taught us much about this previously unknown type of prehistoric site in Montana. Trying to understand why early people killed pronghorns rather than bison, the predominant food staple of early Plains dwellers, poses intriguing research questions.

The almost single-minded reliance by Plains Indians on the American bison is widely known. Bison provided considerable food, and the bones, horns, hooves, sinew, and hides afforded a hardware-store-like stock of raw materials essential for life support. The special relationship between bison and early humans - that of prey and predator - began at least 11,000 years ago on the High Plains, ending when bison narrowly escaped extinction in the late 1800s.

That long-term dependency on bison notwithstanding, Plains herbivores such as the pronghorn were essential to support human life, especially during unexpected food shortages. Summer droughts that caused bison to abandon their customary winter range in river valleys led to predation by hunters on "lesser" local prey species. Such adaptations to short-term (or even to protracted) climatic fluctuations involved hunters turning to pronghorns, deer, elk, and bighorn sheep for food.

Plains bison hunters were familiar with the peculiarities of pronghorn behavior and that of other medium-sized and larger species. Of the potential Plains prey, pronghorns were co-dominant with bison. Both are gregarious herbivores that periodically congregate in large herds, pronghorns during the winter. Pronghorns were much smaller than bison so they provided less meat, smaller hides, and fewer raw materials for toolmaking.

In the course of bison drives, pronghorns were occasionally killed by becoming entangled in the stampeding bison herd and falling to their death from a precipice. However, selection of pronghorns as the main prey by regional prehistoric hunters was first documented when the Montana State University (MSU) group identified, recorded, and began to study the Lost Terrace site in 1975.

That year, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) was expecting that the Missouri River, from Fort Benton to the western end of Fort Peck Reservoir - the last free-flowing reach of 149 river miles - would be designated by Congress as a National Wild and Scenic River. The BLM contracted with MSU personnel to identify and record prehistoric and historic sites in this area. We also surveyed possible locations for recreational developments off the river, anticipating stepped-up visitation by recreating river users. An archaeological survey of part of that area by the River Basin Survey of the Smithsonian Institution in 1962 had recorded 55 archaeological and historical sites between Fort Benton and Armells Creek, a distance of 160 river miles.

MSU fieldwork by boat and on foot began in the very wet late spring of 1975 at Virgelle and ended two weeks later 128 miles downriver at the James Kipp State Recreation Area. We recorded 129 heritage sites in the eroding floodplain and on adjoining river terraces and slopes. Five important sites, including Lost Terrace, were test excavated to assess their importance and to provide knowledge about early human settlement patterns and resource use in the river valley.

Lost Terrace had been partly destroyed by the scouring action of ice jams, erosion of underlying sands, and by slumping. Radiocarbon dates on wood charcoal from the midden dated the remaining deposits to the Late Prehistoric Period, about 1,000 years ago, where they were later buried by alluvium from intermittent flooding.

Jack Fisher, an associate professor of anthropology at Montana State University-Bozeman, determined that demolished bones and lower jaws retrieved by excavation represented a minimum of 83 adult and subadult and 25 unborn pronghorns; his estimate was based on counts of lower foreleg bone fragments and ankle bones. Modern pronghorns in the Missouri Breaks are born from May 15 to June 1, after a 252-day gestation. Since the fetal pronghorns at Lost Terrace were short of full term by three to four months, they died in mid- to late winter, according to Michael Wilson, collaborating zooarchaeologist, an associate professor of geology at Douglas College in British Columbia, Canada.

|

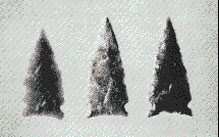

Figure 1 - Arrowpoints produced and used by Avonka Complex bowmen are quite small, symmetrical, and thin. The shallow side-notches were placed low on the point above the base, consistent with the Avonlea notion of the ideal arrowpoint (MSU photo) |

Fisher, my co-worker in the protracted Lost Terrace research effort, also identified a butchered white-tailed deer hock joint and bones of a single bison. Wilson identified the broken bones of a crow-sized bird. The deer, bison, and bird remains are regarded as scavenged carcass parts discarded at the site. Shells of a half dozen freshwater mussels were mixed among the bones and heat-fractured rocks that comprise much of the "garbage" discarded at Lost Terrace.

Thin, triangular arrowpoints (Figure 1) found at Lost Terrace are identical to points produced by flint-knappers of the Avonlea cultural phase in the Northwestern Plains of North America.

Recognized and first dated at about 1500 B.P. (years before present) at a bison kill site near Avonlea, Saskatchewan, these distinctive arrowpoints have since been traced throughout the Plains and Rocky Mountains of Montana. The Avonlea Complex is characterized as small extended family groups of seminomadic hunter-gatherers who exploited various game and other resources seasonally, but who usually relied on bison in both plains and mountainous areas. The Avonlea arrowpoint is widely accepted as evidence for the arrival of bow-and-arrow technology in the Northern Plains, following its introduction into the Americas from Asia. Those who used Avonlea points were succeeded by peoples who continued to use bows-and-arrows for hunting, who occupied a similar area, and who also pursued bison successfully.

That Avonlea hunters were adept with the bow-and-arrow is evident at many sites where bison were driven off steep cliffs or into corral-like containments constructed below short drop-offs or at the end of grassy swales. The Timber Ridge bison kill site south of Chinook, on the north slope of the Bearpaw Mountains 50 miles northeast of Lost Terrace, is an excellent example. There, bison were driven across level terrain into a circular impoundment formed by posts imbedded in the ground; poles lashed horizontally between the uprights completed the trap. Bison killing at Timber Ridge occurred about 1000 B.P., around the time that pronghorns were exploited at the Lost Terrace site. Unfortunately, the season when the Timber Ridge Avonlea bison kill was operated cannot now be determined since the deposit was destroyed by artifact collectors years ago.

We cannot know directly the manner in which pronghorns were procured for human use at Lost Terrace. We do know that historic Montana Natives such as the Flathead, Blackfeet, and Assiniboine lured them into prepared pits or corrals--by intercepting them along well-established trails or while they were swimming a river or crossing a frozen river on the ice.

Today, pronghorns in the area disperse into local groups in the autumn, but band together in winter to form herds of 20-100 animals. Bucks join the doe-fawn herds after extreme weather sets in. As snow covers feeding areas, pronghorns move to exposed ridges were vegetation is still accessible or down into breaks, coulees, or onto the valley floor of major drainages. Browse (big sagebrush, fringed sagewort, silver sagebrush, rabbitbrush, and other species) comprises up to 98 percent of their winter feed.

|

Figure 2 - Swiss artist Karl Bodmer, while traveling as a member of the Maximilian Expedition in 1835, recorded pronghorns crossing the Missouri River only a few miles from Lost Terrace |

Winter-weakened pronghorns could have vacated the prairie uplands in search of the sheltering gullies and box canyons behind Lost Terrace. They probably tried to find browse and respite from bitter winds at a south-facing location. Well-traveled trails down from the uplands, which crossed the river near Lost Terrace, would have funneled moving pronghorns close by. Bob Ottersberg, cooperating soil scientist from Eugene, Oregon, suspects that the river was exceptionally shallow at that particular point and it may have been a crossing place for herds of pronghorns (Figure 2) during all seasons.

In spite of their keen sight, acute sense of smell, and great speed, pronghorns were vulnerable to hunters on foot. Although pronghorns could detect moving predators at great distances, even at close range they failed to notice hunters downwind, crouched low and unmoving below the skyline. Pronghorns would approach a moving flag or scarf nervously, possibly to gain the scent and identify the intruder, thus coming within range of waiting hunters' weapons. As well, pronghorns were averse to jumping over fences and could easily be corralled. Their predictable use of certain trails and their tendency to return to locations from which they had been disturbed also allowed patient hunters armed with bows-and-arrows to intercept them efficiently.

We are forced to conjecture about the way early plainsmen took pronghorns trailing northward from south of the Missouri River--probably while traveling in single file along a well-used game trail. Hunters concealed behind nearby river cutbanks might have ambushed pronghorns at close range. Or pronghorns trailing southward from the uplands were intercepted by hunters positioned out of sight along the trail. The animals could then have been diverted into one of the adjacent box canyons where vertical volcanic dikes served as restraining walls; they were then cut off, captured, and killed inside the natural enclosure. Silent hunters drew, aimed, and released arrows without unduly alarming the always alert, but unsuspecting pronghorns. Small groups of coordinated hunters moved stealthily to get in close, approaching from downwind and waited unmoving for long periods. Effectively placed arrows brought pronghorns down quickly. Wounded pronghorns were tracked, collected, and brought back. The pronghorn carcasses were then carried to the processing site chosen conveniently next to the river.

In view of the larger populations of pronghorns and low population densities of humans in those times, pronghorns may have been even less difficult to approach, deceive, and bag than they are for bowhunters today who are equipped with more sophisticated equipment. Early hunters likely relied more on their ability to stalk, ambush, drive, and capture game than on the precision of their hunting equipment. We can glean only a few facts about their hunting equipment from evidence at Lost Terrace. We must infer most features by analogy to the bows-and-arrows of historic Indians. Arrow shafts were made from green serviceberry wood or from willows. Simple wooden bows were made from ash or other durable yet resilient wood backed with sinew. Bowstrings were made from twisted sinew. Three or four hawk or upland bird feathers were tied around the rear one-third of the arrow shaft to stabilize it's flight. Bows-and-arrows were carried over the shoulder in a quiver made from otter or cougar hide.

|

Whatever bows-and-arrows actually looked like, pronghorns at Lost Terrace were killed and exhaustively utilized by hunters. While the breakage and shattering of major grease and marrow-bearing bones was a common subsistence practice among many big game hunters, the extent to which bones were pulverized at Lost Terrace suggests famine and severe nutritional stress. Fisher's analysis of the number of pronghorns processed at Lost Terrace was complicated by the extreme breakage: not a single limb bone survived intact. It is difficult to reconstruct the way in which the carcasses were skinned, dismembered, and cut up since most of the cut marks that reveal butchering practices had been obliterated. |

Above: Illustration of a Native American bow hunter (by Bob Edgar) |

Lost Terrace was primarily a food processing site, but hide preparation and stone tool production, resharpening, and maintenance also occurred there. Cold temperatures would have complicated the scraping and tanning of hides into usable skins. Occasional warming by short-lived chinook winds might have eased that problem without thawing the stores of frozen, smoked, or air-dried pronghorn meat. The hundreds of pounds of fire-broken rocks amidst the discarded bones reflect use of fires to smoke hides and meat, to boil meat eaten on the spot, to extract bone grease and marrow, and to warm hands chilled by Arctic winds.

The Avonlea Complex toolkit sample recovered at Lost Terrace is remarkably impoverished - only a few tools are present, and they are small, almost miniature. Since quality stone was not abundant nearby, the people used their reserve supplies sparingly. We found arrow points, knives, scrapers, a tongue-shaped core and waste flakes, a cobble chopper, a grooved hammerstone, and a broken sandstone arrowshaft smother. All but the arrowpoints and arrowshaft smoother were used in food- and hide-processing. The core and waste flakes are discarded by-products of stone tool production and maintenance. Sally Greiser, cooperating lithic analyst in Missoula, was impressed by the careful, economical use of stone when she studied those artifacts as geological products, as toolmaking raw materials, and finally as tools produced and used at Lost Terrace. That stone raw materials were in short supply and used sparingly is consistent with the late winter food shortage hypothesis presented here to account for evidence available from Lost Terrace in the 1970s.

The nearly exclusive resort to pronghorn meat and hides at Lost Terrace was likely a consequence of short-term climatic changes that had caused summer droughts. Under such conditions, bison herds that usually assembled in nearby river bottoms during the winter instead sought needed food elsewhere. They broke up into smaller herds to survive, dispersing and moving beyond the reach of a hungry, expectant people weakened and slowed by winter conditions. Impending disaster was averted because resourceful bowhunters managed to harvest a group of winter-stressed pronghorns. The carcasses obtained were utilized exhaustively to carry famished peoples through this crucial period. The pronghorns served a life-giving role in an emergency situation by providing food for people endangered by severe weather and winter famine.

Some historic Plains Indians resorted to hunting pronghorns during winter months. The Kiowa, for example, conducted pronghorn drives when food was scarce, but only during winter when pronghorns gathered in large herds. The Assiniboine hunted pronghorns and smaller game along wooded river bottoms where shelter and fuel were available, even when sufficient meat and tallow were in winter storage. It is, therefore, possible that events at Lost Terrace were a product of a routine, seasonally proscribed hunting practice rather than a response to unusual environmental conditions.However, until we can find and study other Avonlea pronghorn kill and processing sites, evidence developed by Lost Terrace research may be best explained as a response to an atypical winter crisis by determined hunters.

Today, the Lost Terrace archaeological site--a unique cultural resource in the Northwestern Plains region of Montana--continues in jeopardy as erosion persistently carves that fragile floodplain. This deteriorating, significant heritage site has posed a challenge to agency administrators and cultural resource personnel responsible for its management. Investigations carried out during the summer of 1985 at Lost Terrace helped significantly to mitigate the loss of culture-bearing deposits. Prehistoric human behavior at Lost Terrace is becoming better understood through research. Continue to the next page, Pronghorn.

This article, reprinted with permission from the editor of Montana Outdoors Magazine, is revised.

Back to Animals Home Page.